Every number can be equal to 0

An exploration of modular arithmetic and the nature of numbers in different systems.

Every number can be equal to 0.

You think this is completely absurd.

But it's possible.

2 can be equal to 0.

143 can be equal to 0.

can be equal to 0.

And all of this is not some theoretical oddity never used in practice.

You even use these mathematics daily.

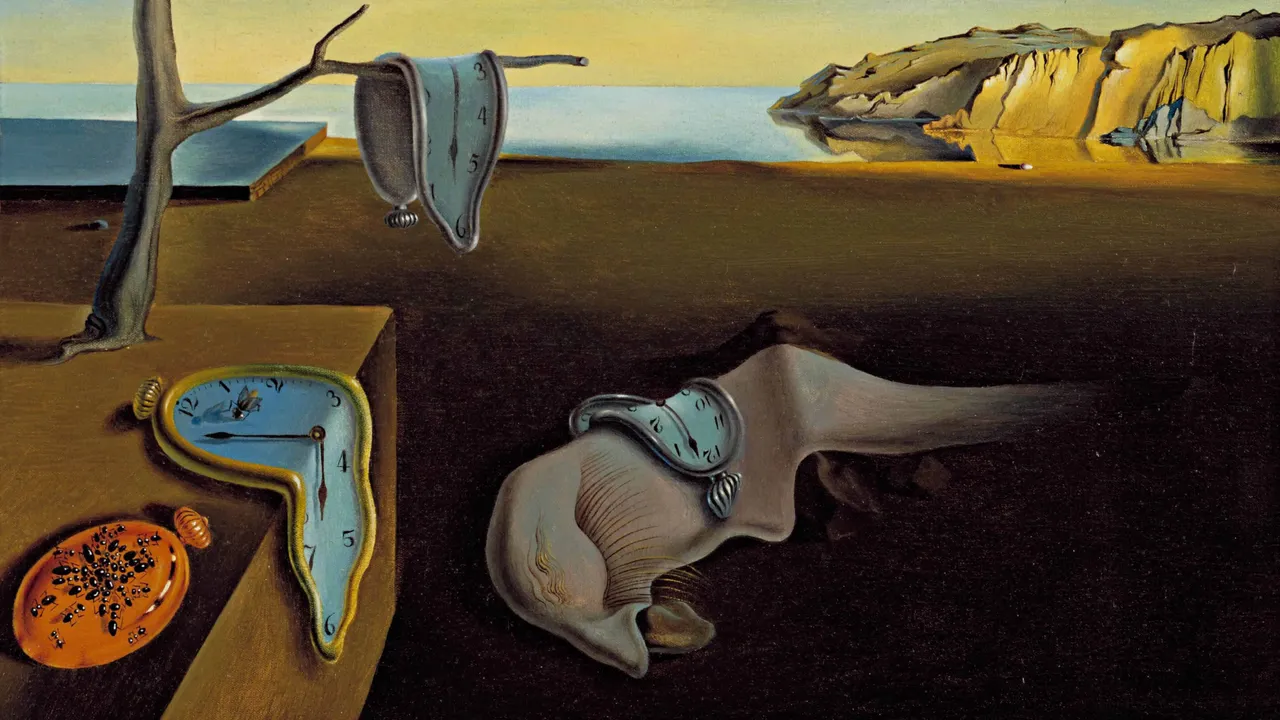

To give you a direct example, when you count time on a clock, you're doing modulo 12 arithmetic.

Clock arithmetic

In this case, .

In this case, .

More generally: Since all these numbers are equal to 0, it means that for each number (hour) you can add or subtract a multiple of 12 and you'll fall back on the same number (the same hour).

Let's perform some operations:

Addition:

So and are opposites, in other words, and . Interestingly, So is its own opposite: .

Multiplication:

Here's a surprising fact: a number squared (different from and ) is equal to itself.

But also:

So , , and are their own inverses.

Even more surprising: The product of two non-zero numbers is zero.

What we did with 12 can be done with any other integer , you just need to imagine a clock with hours.

All of this is intriguing and fascinating, while being easily accessible, so why is it so little known, why is it that, if not taught, it's not even mentioned in school?

The problem of mathematics teaching in school

One problem among many in school mathematics teaching is that it reveals an extremely confined portion of the mathematical landscape and leads one to presuppose that this truly represents all of mathematics.

We end up with this kind of clichés:

-

There are infinitely many numbers.

-

True in , false in . (Clock arithmetic)

-

You can't count beyond infinity.

-

Except with transfinite numbers.

-

Every squared number is positive.

-

This is false with complex numbers: .

It is intellectually weak or dishonest to teach a theory without mentioning its limits, its extensions, and related or competing theories.

Construction of modular arithmetic

Let's now see rigorously how the number 2 can be equal to 0.

Because by definition:

- 0 is not the successor of any number

- 1 is the successor of 0.

- 2 is the successor of 1 So 2 is different from 0.

And all of this is exact.

But this is true in the arithmetic of natural numbers formalized by Peano, verifying the following axioms:

Peano's axioms

- The element called zero and noted is a natural number.

- Every natural number has a unique successor, noted , which is a natural number.

- No natural number has as its successor.

- Two natural numbers having the same successor are equal.

- If a set of natural numbers contains and contains the successor of each of its elements, then this set is .

But one can construct a multitude of number systems with different arithmetics...

After all, nothing says that these arithmetics will be interesting.

In everyday life and in science, Peano's arithmetic deserves its central place.

But one must always keep in mind that it's a particular system and that others exist.

Moreover, most of these other systems can be constructed from Peano's arithmetic.

This is the case of arithmetic of integers modulo or more vulgarly, clock arithmetic with hours.

Appearance of equivalence classes

Let's treat the case .

You start from the set of integers with Peano's arithmetic.

You introduce an equivalence relation:

Two numbers are equivalent if and only if their difference is divisible by 2.

This amounts to identifying as equivalent all even numbers and as equivalent all odd numbers.

Equivalence classes become numbers

And the ingenious idea is to treat these equivalence classes of numbers... as numbers.

We still need to see if this gives something interesting and coherent:

Can you give meaning to the operations and ?

In other words, are the following equalities true?

For addition:

For multiplication:

I'll let you verify for yourselves that these equalities are indeed valid. (The simplest way is to use the fact that every integer can be written, based on its parity, in the form or with .)

Since these equalities are true for every even number and every odd number, we can choose a representative for each class.

For example, 42 for even numbers and 137 for odd numbers.

But of course, we generally do much simpler and take 0 for even numbers and 1 for odd numbers.

I insist, from here on, represents all even numbers and represents all odd numbers.

Our equalities then become:

For multiplication:

And we have an arithmetic system composed of two elements noted and (representing in reality the 2 parity classes), and two operations and .

Since every number has an opposite and every number different from has an inverse, we also have the operations and that follow.

This number system, which we generally note either:

- to emphasize its construction: The quotient of by even numbers .

- to emphasize that it's a field () with two elements (there's only one).

Opening

This same construction is valid for any natural number .

Again, with , we get clock arithmetic or .

But in this case, this arithmetic system is not a field.

Because although every number has an opposite.

There exist numbers (non-zero) without inverses.

After verification, we see that these are the numbers 2,3,4,6,8,9, and 10.

That is, all numbers having divisors (different from 1) in common with 12.

In other words, these are all numbers not coprime with 12.

This leads us to the starting point of finite field theory:

Theorem: Let be a natural number, then is a field if and only if is a prime number.