Why is everything false?

An exploration of the nature of truth and the limits of knowledge.

Or why is nothing true?

If these questions shock you, it's because you still have the illusion that, even if you don't hold all the truth, you have at least acquired some of it during your existence.

If that's the case, what follows may be disconcerting...

Since you're so attached to truth, let's look at its definition.

I. The dictionary game

Truth: "Knowledge conforming to reality"

So truth is linked to reality, but what exactly is reality?

Reality: "That which actually exists"

Thus, reality refers to existence, but concretely, what does it mean to exist?

Exist: "To have reality."

And if the loop isn't already clear enough:

Reality: "The quality of being real, of actually existing"

And here is an Ouroboros, or a snake biting its tail, or an infinite loop. Call it what you want, the result is the same: you're going around in circles indefinitely.

Want another ticket?

Want another ticket?

Table ⇨ furniture ⇨ object ⇨ thing ⇨ concrete or abstract reality ⇨ real ⇨ exist ⇨ reality ⇨ real 🔄

And off we go again in an infinite loop.

By the way, I'm willing to bet that you can take any word in the dictionary and eventually end up in this infinite loop.

Which can be summarized by the following tautology: "What is, is"

Having seen this, it seems surprising that we're able to think rigorously and express sensible words. But are we really capable of such a feat, or is it just an illusion?

II. Agrippa's trilemma

If you seek to prove any "truth" (assuming that makes sense) and you sincerely examine your argument, you'll realize that it's either:

Circular: you justify your argument with... your argument.

An infinite regression: your argument rests on an argument that rests on an argument, and so on, infinitely.

Dogmatic or transcendent: like infinite regression, except at some point you stop and say: "This is true, I don't need an argument to prove it and that's that."

A nice legend wonderfully illustrates infinite regression.

After a conference dealing with cosmology and the solar system, the speaker's discourse is challenged by an old lady.

"Sir, your theory stating that the sun is at the center of the universe, and that the earth is a round ball that revolves around it, is almost convincing. But all of this is false, and I have a much better theory."

"Oh really? In that case, please, share your theory with me."

"My theory is that in truth, we live on an earth crust that rests on the back of a giant turtle."

The speaker, not wanting to brutally dismantle the old lady's completely absurd theory, decides to play along.

"But, and I don't doubt it for a second, if your theory is correct, what does the giant turtle rest on?"

"Your question proves you're a very intelligent man. But the answer is simple, the first turtle stands on a second turtle, much larger than the first."

Annoyed, the speaker replies,

"If I ask you what this second turtle rests on, I imagine you'll tell me it stands on another larger turtle. So let's cut the childishness and tell me what the last turtle rests on?"

The old lady smiles and calmly replies,

"Sir, I don't think you understand. It's turtles all the way down"

This way of categorizing every proof into one of these three categories is called Agrippa's trilemma (Agrippa the skeptic was a Greek philosopher who lived around the end of the 1st century AD), or called Münchhausen's trilemma, in reference to the baron of the same name, known for his stories all more absurd than each other. Including one, in which he claims to have succeeded in pulling himself and his horse out of quicksand (hold on tight) by lifting himself by his hair.

This way of categorizing every proof into one of these three categories is called Agrippa's trilemma (Agrippa the skeptic was a Greek philosopher who lived around the end of the 1st century AD), or called Münchhausen's trilemma, in reference to the baron of the same name, known for his stories all more absurd than each other. Including one, in which he claims to have succeeded in pulling himself and his horse out of quicksand (hold on tight) by lifting himself by his hair.

(What kind of argument is this?)

III. Truth in mathematics

It's interesting to look at how human fields of study are constructed, and it seems they are all founded on a dogmatic or transcendent argument.

Take theology for example, which is the study of the divine and therefore of God. Now God is generally defined as "first principle" or "first cause". This is the very definition of a transcendent argument (and in fact, it's more or less what the idea of transcendence points to).

Mathematics is no exception to the rule.

Mathematics is constructed and developed from axioms. And the definition of an axiom is precisely: "Proposition considered as evident, admitted without demonstration".

Thus, these axioms are arbitrary, they are decided by human beings, they can be modified. Moreover, there are several sets of axioms, each giving birth to different mathematics.

Geometry, or more precisely, geometries

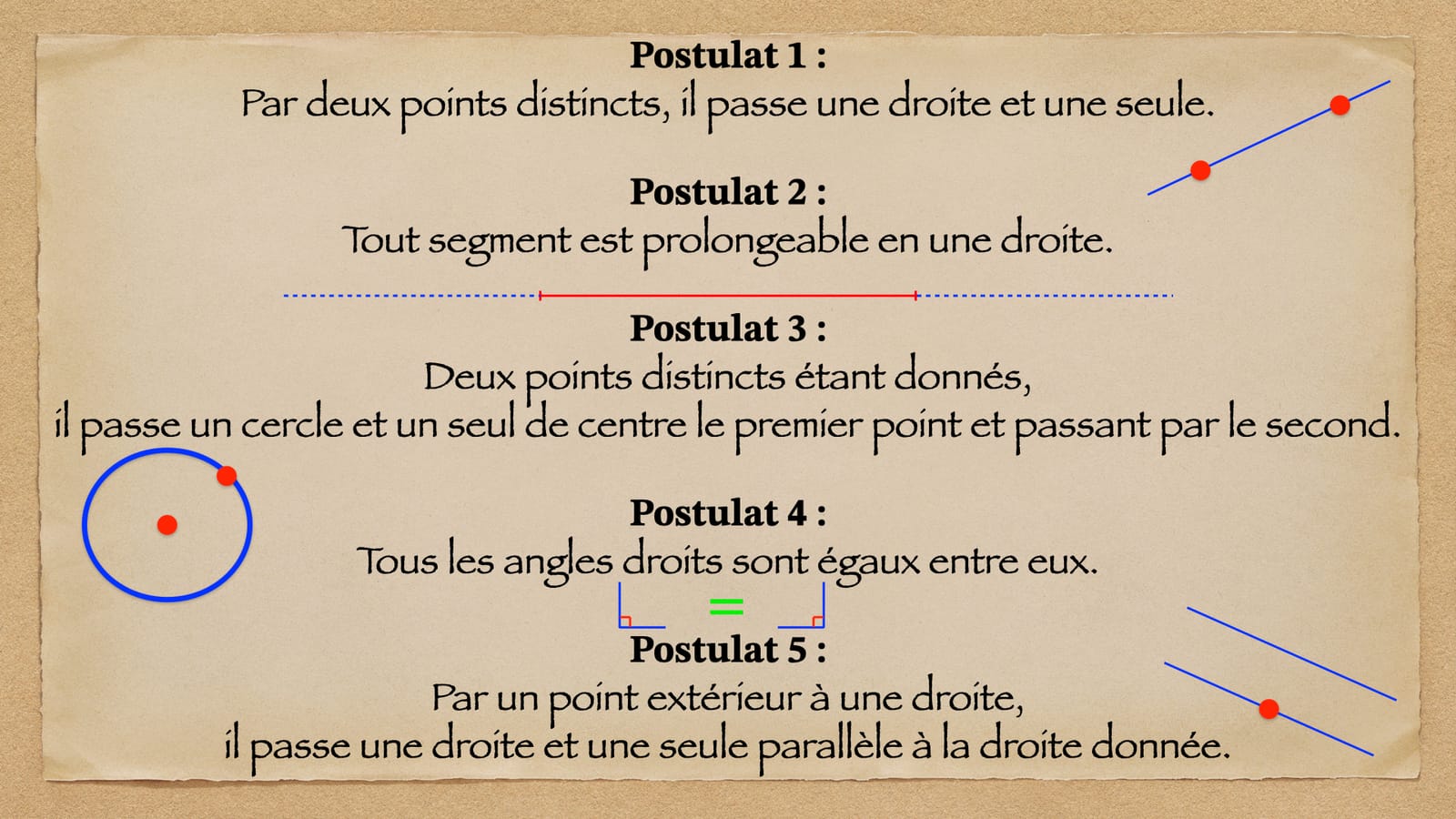

We can think of Euclid's 5 axioms, which he calls postulates:

And which allow us to study so-called Euclidean or plane geometry. Why plane?

And which allow us to study so-called Euclidean or plane geometry. Why plane?

Simply because it unfolds in the plane.

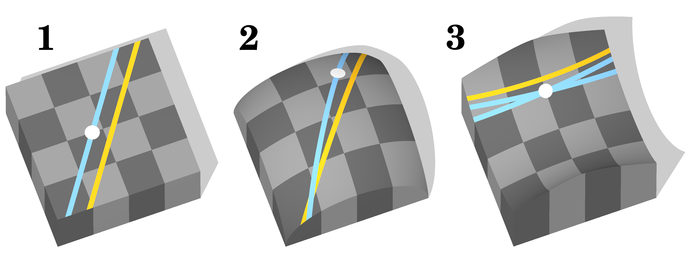

And precisely, if we abandon the 5th Postulate, then we see two new so-called non-Euclidean geometries appear that unfold on curved spaces:

Spherical geometry. Imagine that instead of doing geometry in a plane, you now do geometry on a sphere.

Hyperbolic geometry. This time, imagine that you do geometry on a horse's saddle.

- Euclidean geometry, through a point outside a line, there passes one and only one line parallel to the given line. (5th postulate).

- Spherical geometry, through a point outside a line, every line passing through this point intersects the given line.

- Hyperbolic geometry, through a point outside a line, there exist infinitely many lines passing through this point and parallel to the given line.

Arithmetic of natural numbers

The arithmetic of natural numbers is constructed from Peano's 9 axioms. Fun fact: the 9th axiom, which is the principle of induction, is actually an axiom schema and therefore consists of an infinity of axioms.

Set theory (ZFC)

Modern mathematics rests on set theory, and this theory is based on an axiom system called ZFC, named in homage to mathematicians Zermelo and Fraenkel who contributed to the development of this axiom system.

But then, what does the C in ZFC mean?

In this acronym, C stands for "Axiom of Choice".

This is an axiom that concerns what we have the right to do with infinity and its axiom is extremely controversial.

I'll let Bertrand Russell (1872 – 1970), one of the greatest logicians of all time, explain it to you:

"To choose one sock rather than the other for each pair in an infinite collection, you need the axiom of choice. But for shoes, it's not necessary".

To choose one sock in a pair rather than the other, you have to make a choice.

So the question is, do you assume you have the right to make an infinity of choices?

For shoes, you can decide from the beginning to always take the left shoe.

So in the end, you've only made one choice, whereas you've made an infinity of them for socks.

And here you see that any choice of axiom is purely arbitrary.

And here you see that any choice of axiom is purely arbitrary.

Kurt Gödel destroys all hope of absolute truth

After, and this is where it becomes fascinating, we can do meta-mathematics. That is, do mathematics on the different mathematical theories constructed from different collections of axioms. We can compare them, study them and deduce properties and theorems.

This is exactly what Kurt Gödel did with his incompleteness theorems.

First incompleteness theorem: Any consistent mathematical theory that allows describing natural numbers is incomplete.

If you didn't understand anything, here are some explanations:

A theory is consistent or coherent if, within this theory, one cannot prove a statement and its contrary. Proving a thing and its contrary would be the worst possible thing. Imagine that you arrive at the conclusion that 1 = 0 even though one of the foundations of your theory is that 1 ≠ 0. From there, you could prove anything and everything, and thus the notion of true and false would no longer have any meaning.

A theory is incomplete if, within this theory, there exist statements that can neither be proven nor refuted. This means that these statements are independent of your theory. What's fascinating when you encounter an undecidable statement is that you can decide it's true and in that case establish it as an axiom. Or decide it's false and in that case, establish the negation of the statement as an axiom.

For example, the axiom of choice is an undecidable statement in ZF theory. Mathematicians can therefore add it to the theory as an axiom, but they could also have added its negation. In both cases, it doesn't change the consistency of the theory

More simply, Euclid's 5th postulate is independent of the other 4. If you accept it as an axiom, you get classical Euclidean geometry. If you take its negation as an axiom, you get spherical and elliptic geometries.

Let's recall the 5th postulate: Through a point outside a line, there passes one and only one line parallel to the given line.

Second incompleteness theorem: The consistency of a theory F that allows describing natural numbers cannot be proven within F.

In practice, one can show the consistency of natural numbers (constructed on Peano's axioms) within set theory (ZFC), which largely encompasses natural numbers. And one can prove the consistency of ZFC, by considering the theory ZFC + "there exists an inaccessible cardinal" (Imagine an infinite set, but not just any infinite, infinitely many times infinitely larger than the infinity of natural numbers)

Here are the limits of a mathematical theory, you are forced to use another distinct theory to prove the consistency of the first, then a third to prove the consistency of the second, and since you cannot close the loop (according to Gödel's second theorem), you find yourself justifying the consistency of your first theory thanks to an infinity of theories.

Does this remind you of something?

Yes, yes, it's indeed an infinite regression. We're back to Münchhausen's trilemma.

Thus, it seems the old lady was right: "It's turtles all the way down".