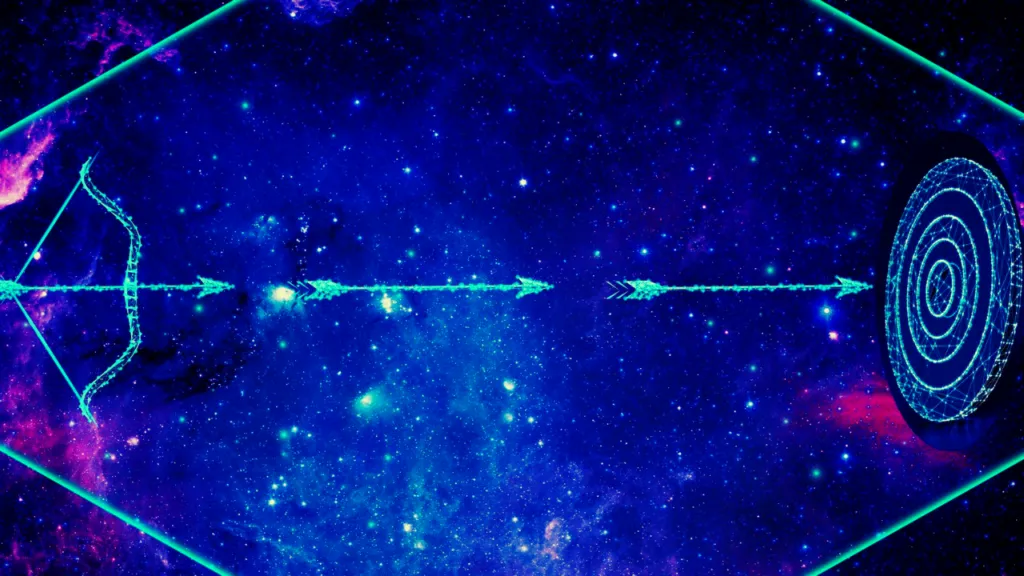

Why does the arrow reach the target?

An exploration of Zeno's paradox and the nature of finite distances divided into an infinity of halves.

Imagine yourself tied to a tree...

In front of you stands an archer, his bow is drawn, his arrow points toward your heart.

This is the end...

Unless...

A strange idea comes to your mind.

For the arrow to reach you,

It must first travel half the distance between you and the bow.

But before traveling that distance, it must first travel half of that distance.

And before that, it must travel half of the previous distance.

And before that, half of the one before.

And before that, half of the one before.

Here is your glimmer of hope,

Since the arrow must travel an infinity of half-distances,

It must travel an infinite distance

Thus, the arrow will never reach your chest.

You breathe a sigh of relief.

At the exact moment the archer releases the string,

Here you have a second flash of genius.

The arrow must not only travel an infinity of half-distances,

It must do so in an infinity of half-time intervals!

The arrow must travel an infinite distance in infinite time.

There you are, convinced.

You are safe and sound.

A fraction of a second later,

The arrow pierces your heart,

Your lips barely have enough strength to stammer

"How is this possible?"

Before you collapse, inert.

This paradox is one of the most famous Greek paradoxes, and is attributed to the philosopher Zeno.

We find it in various forms:

- The paradox of Achilles and the Tortoise

- The dichotomy paradox

- The arrow paradox

In all cases, the paradox is the same:

How can a distance or time be finite when they can be divided into an infinity of halves?

From a physical point of view, this paradox is not resolved.

Because behind this paradox lies the question of the nature of time and distance.

Are these quantities continuous or discrete?

Mathematically, this amounts to asking whether the set that represents them is equinumerous to or to .

And in fact, depending on the continuum hypothesis, there could even be something between the discrete and the continuous.

So let's tackle this problem from a purely mathematical point of view.

We divide an interval, whether it's a distance or time, into an infinity of halves and we tell ourselves that the sum of these infinite halves is infinite.

But this is completely false.

The sum corresponding to taking half, then half of the half, then half of half of the half, etc.

Mathematically, this amounts precisely to calculating:

Yet this infinite sum equals…

A finite number.

Calculating this infinite sum is trivial for anyone who knows geometric series.

Nevertheless, detailing and rigorously explaining this calculation requires making the underlying mathematical concepts explicit, and this demands a non-negligible (but finite) amount of time.

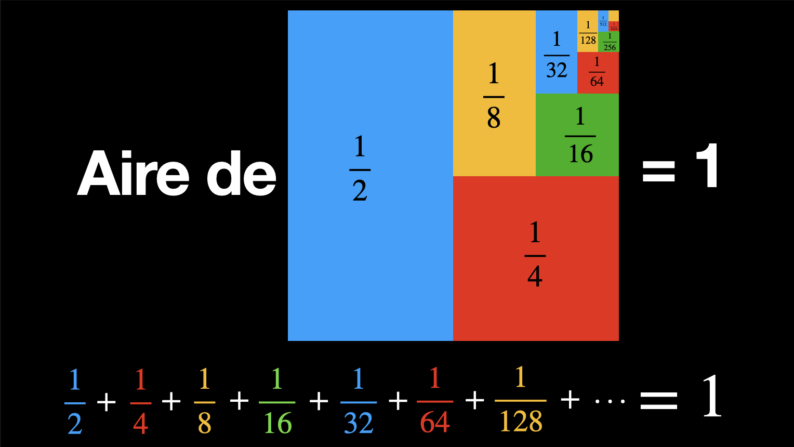

However, the result can be very easily intuited geometrically.

We take a square with side

So the area of this square equals

If we cut this square into two equal parts and take the first half of this square, we get an area of

If we take half of the second half of this square, we get an area of

And continuing thus successively, we obtain an infinity of areas whose sum equals:

Yet this infinity of areas, by construction, covers the entire square.

And since this square has an area of ...

We finally have:

More clearly with an image:

And even more clearly with a video:

And even more clearly with a video: